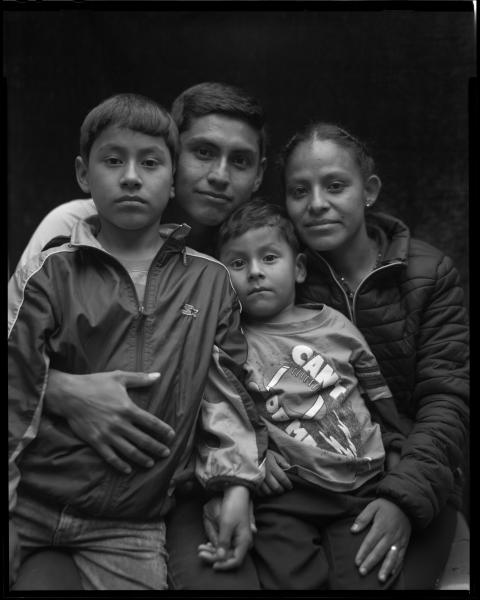

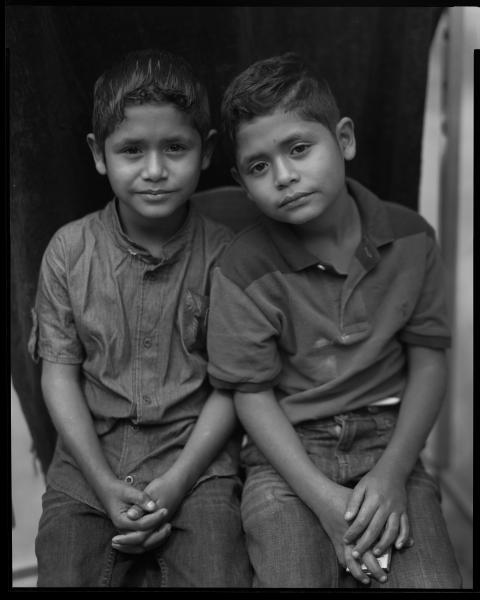

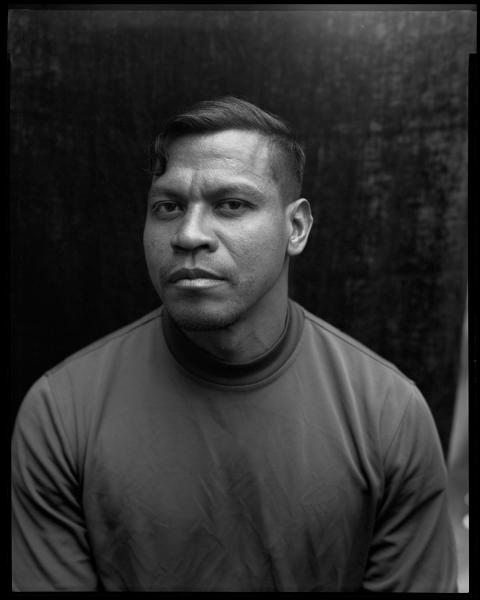

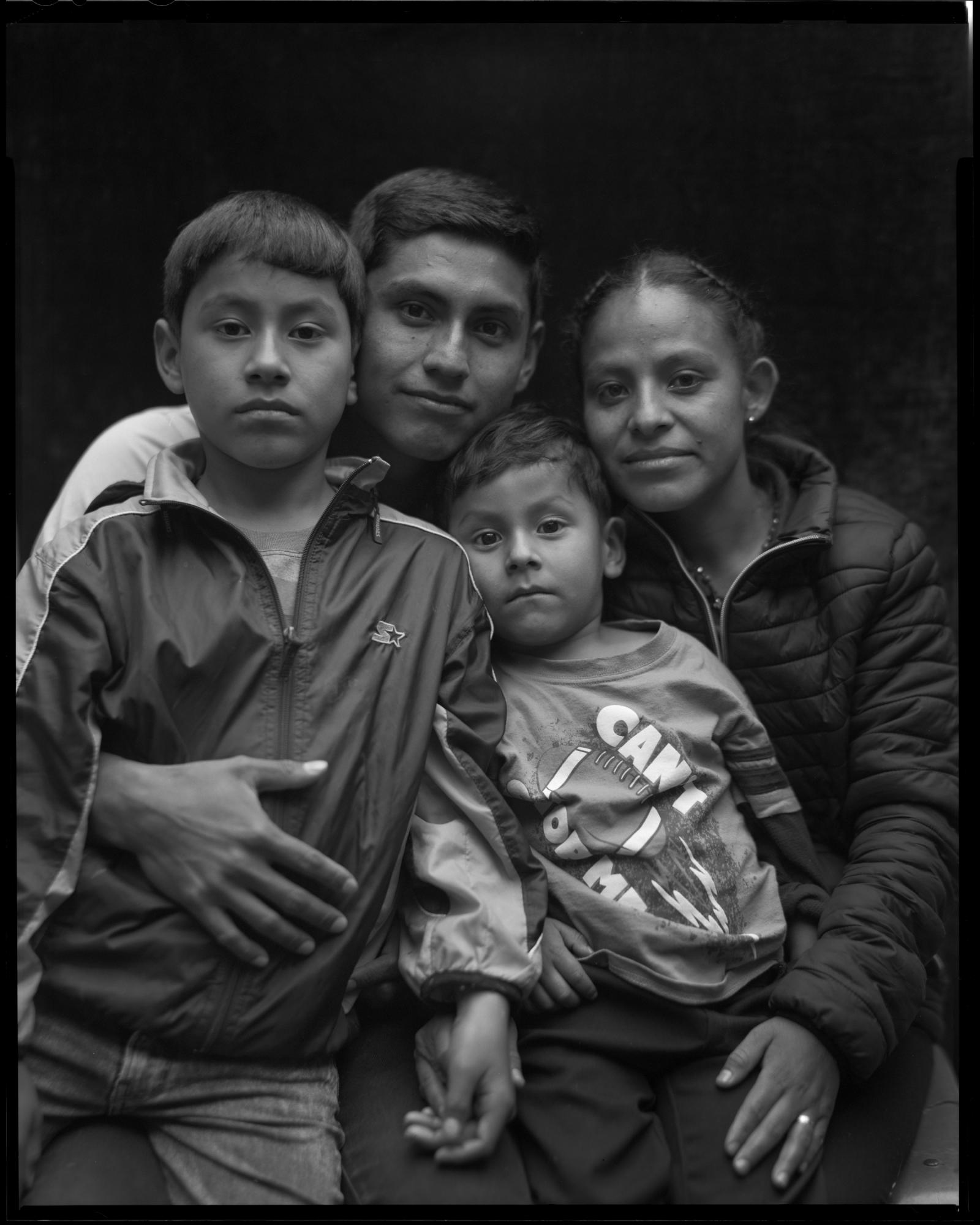

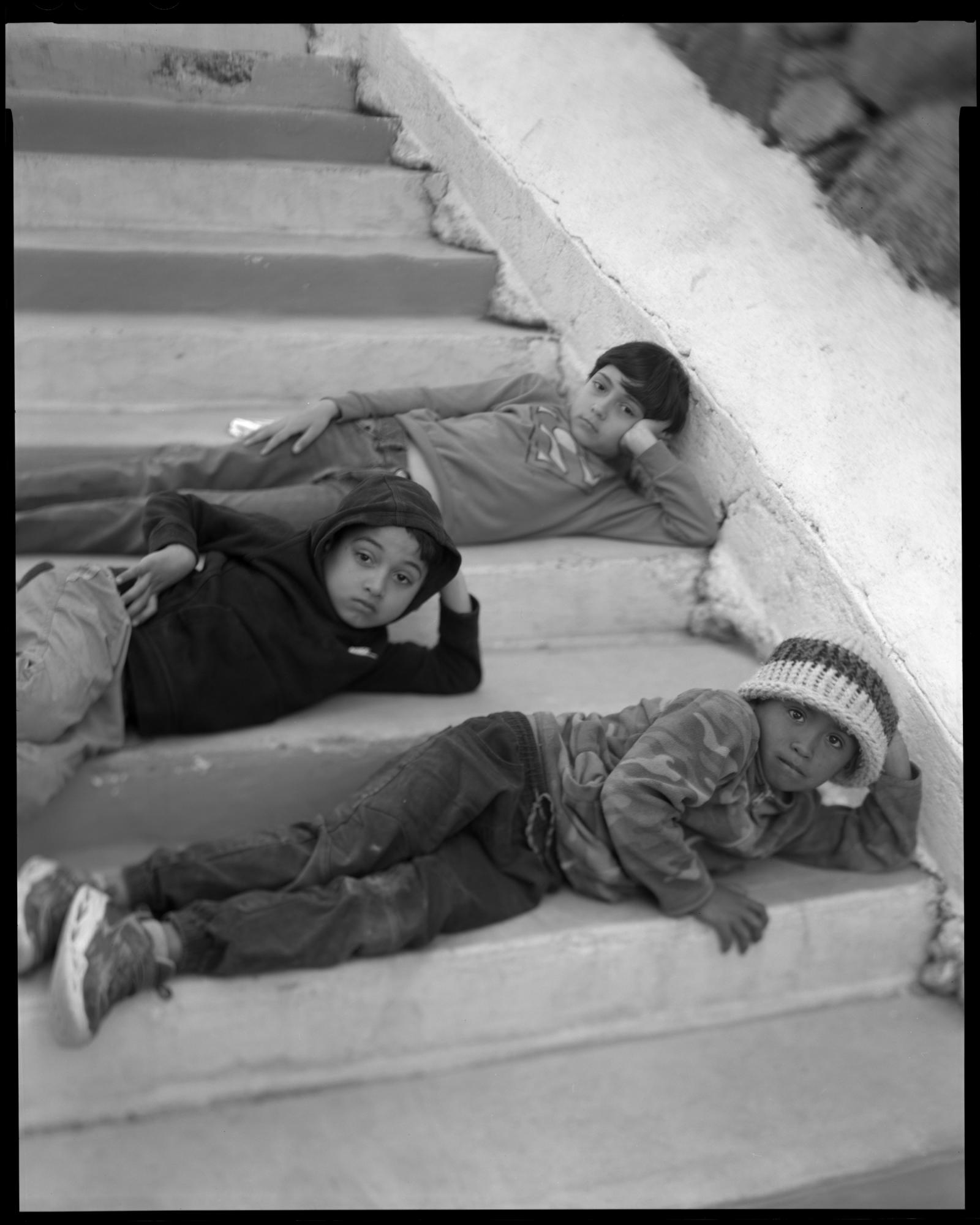

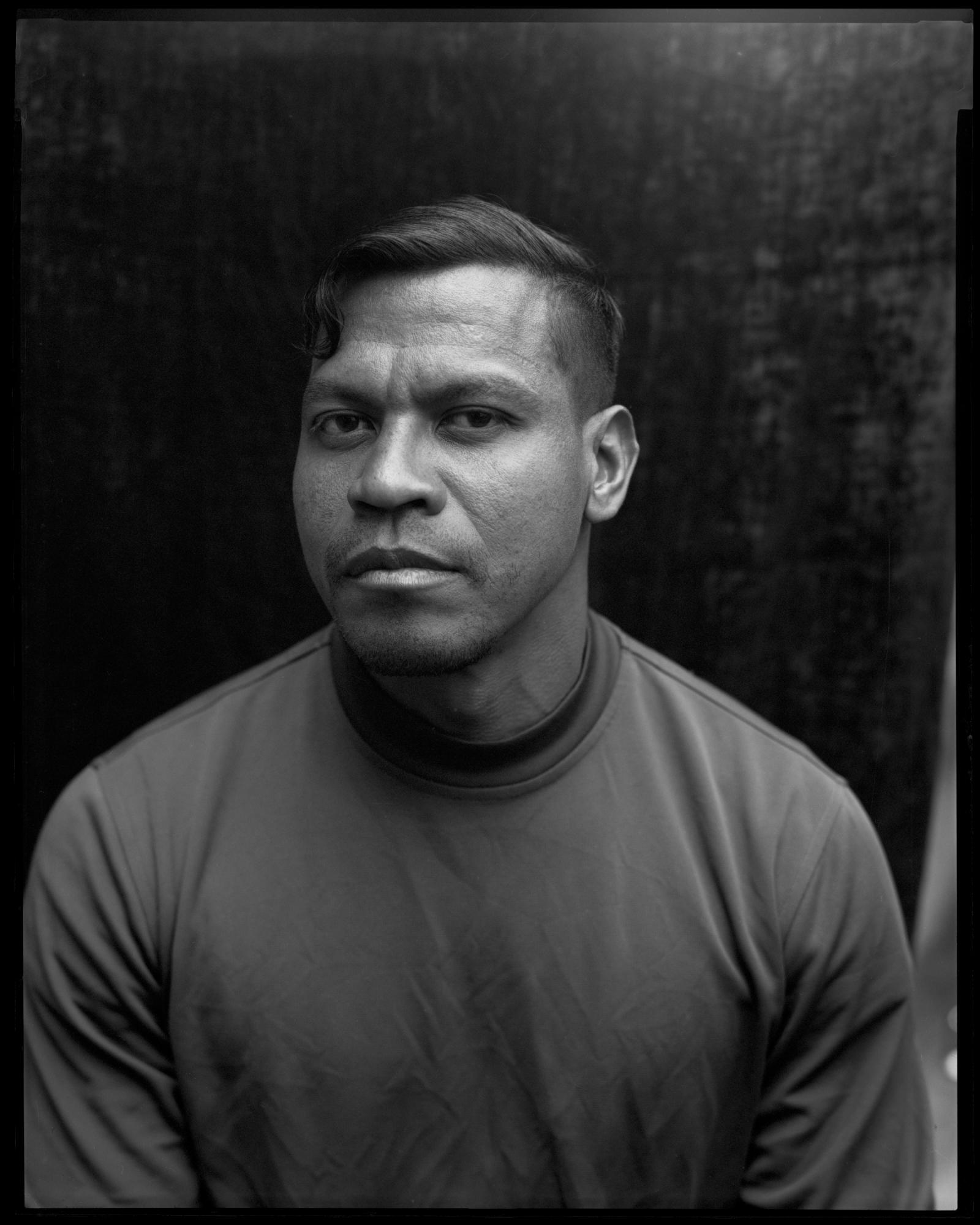

“I don’t care for the American Dream. I didn’t want to leave my home, family, or entire life. I was forced to.”- Blanca, 34, Guerrero, Mexico.

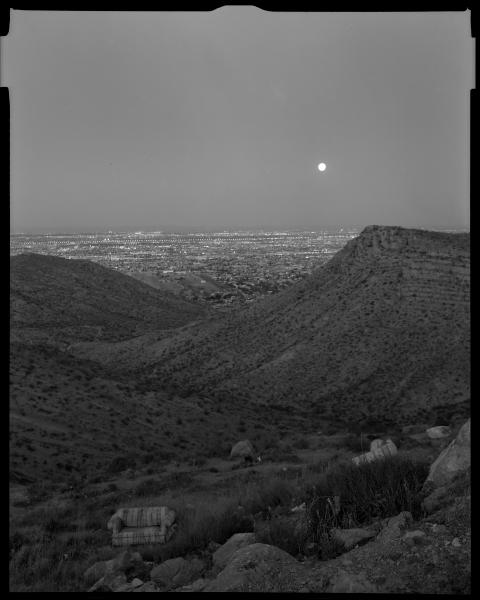

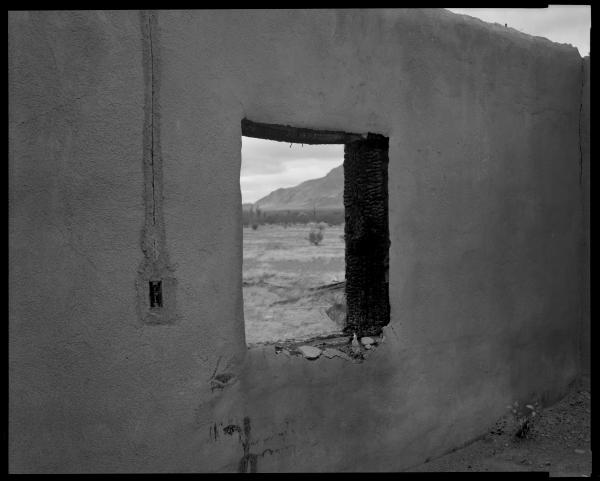

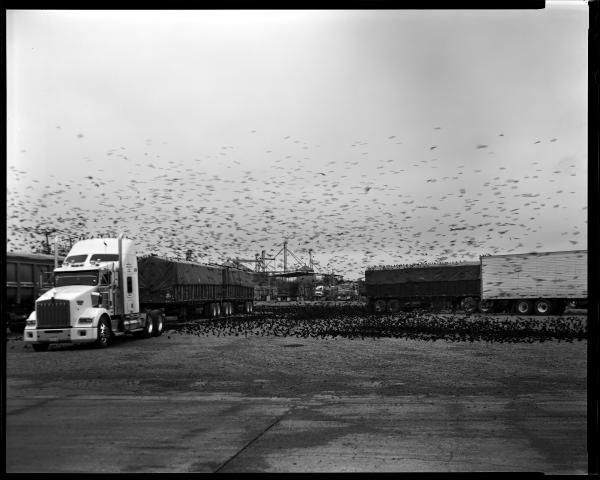

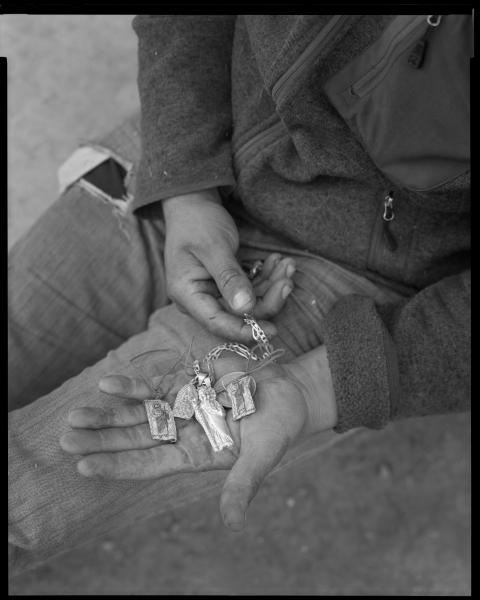

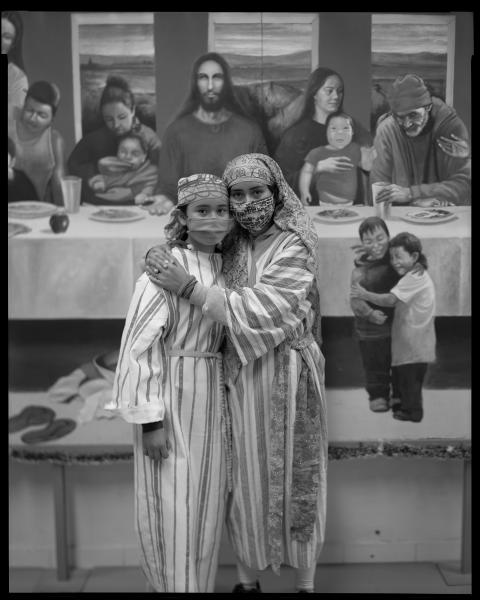

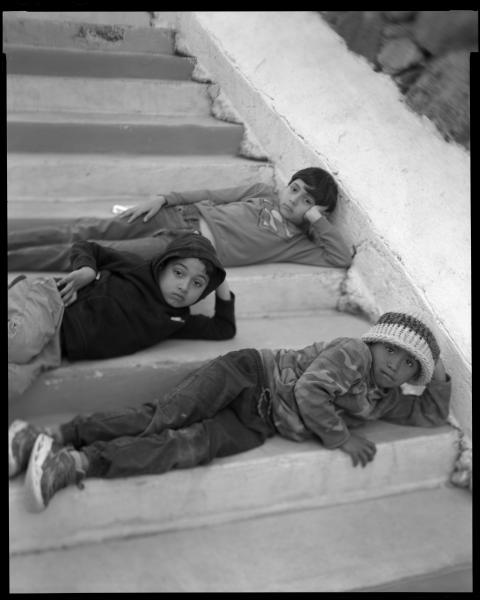

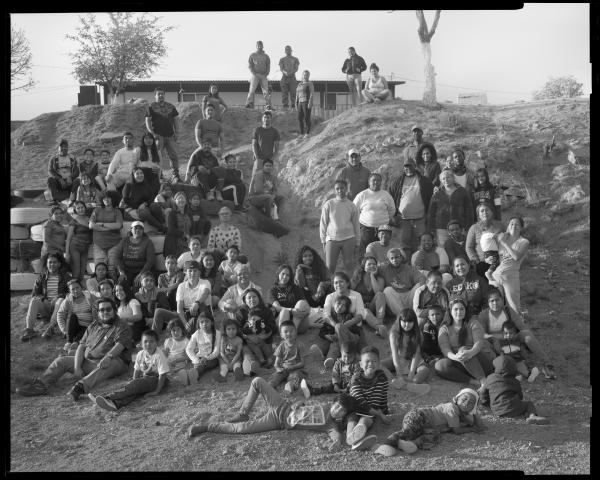

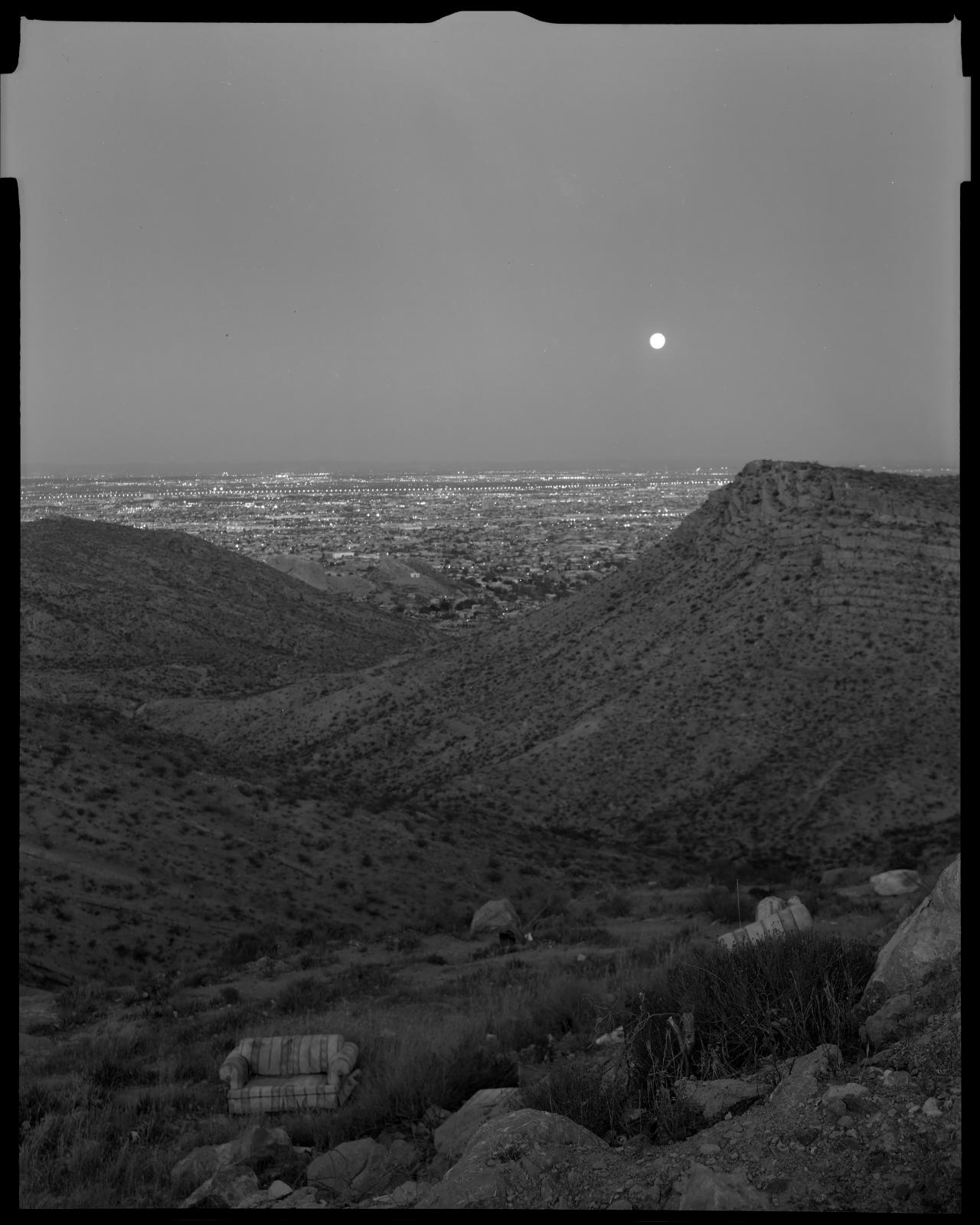

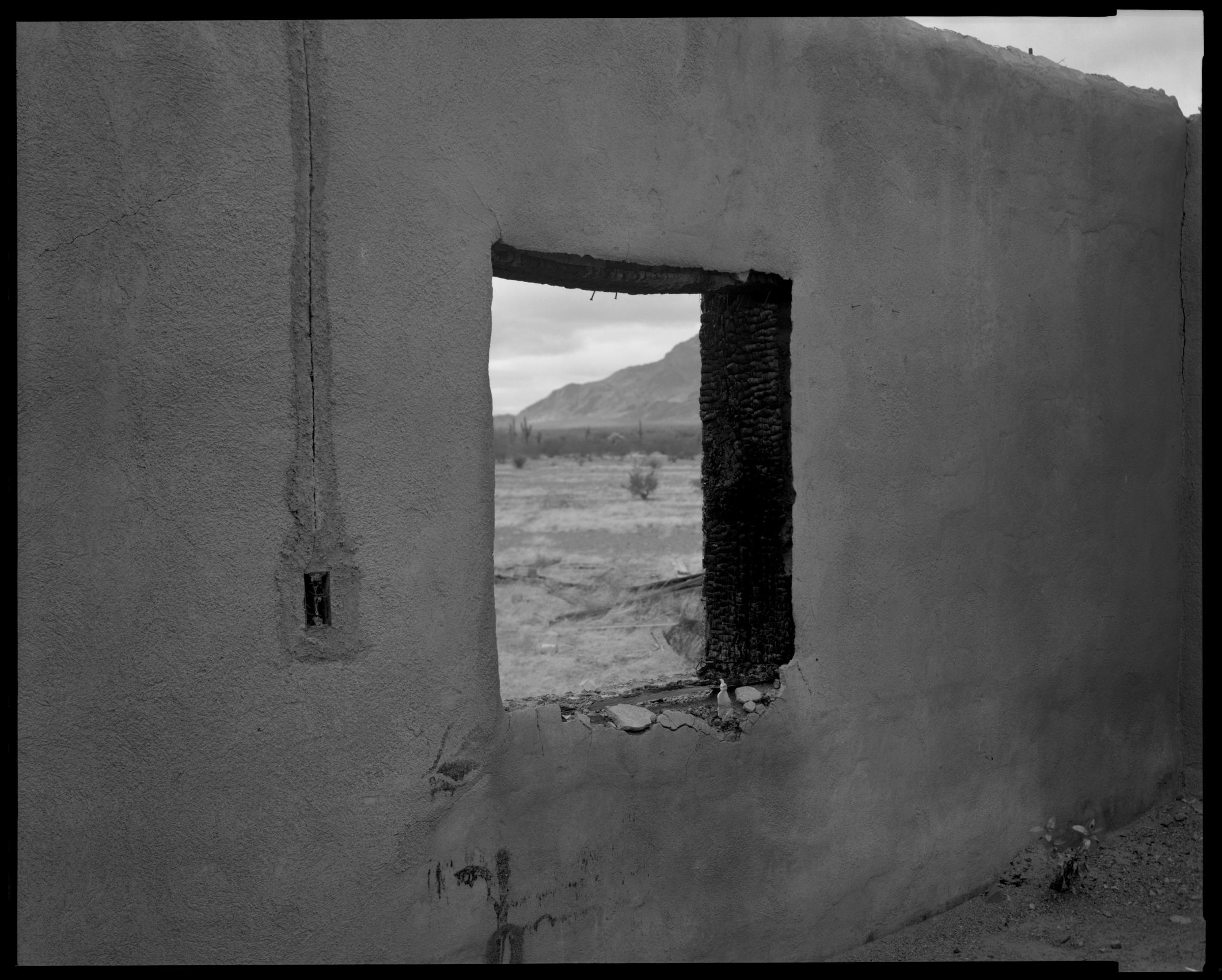

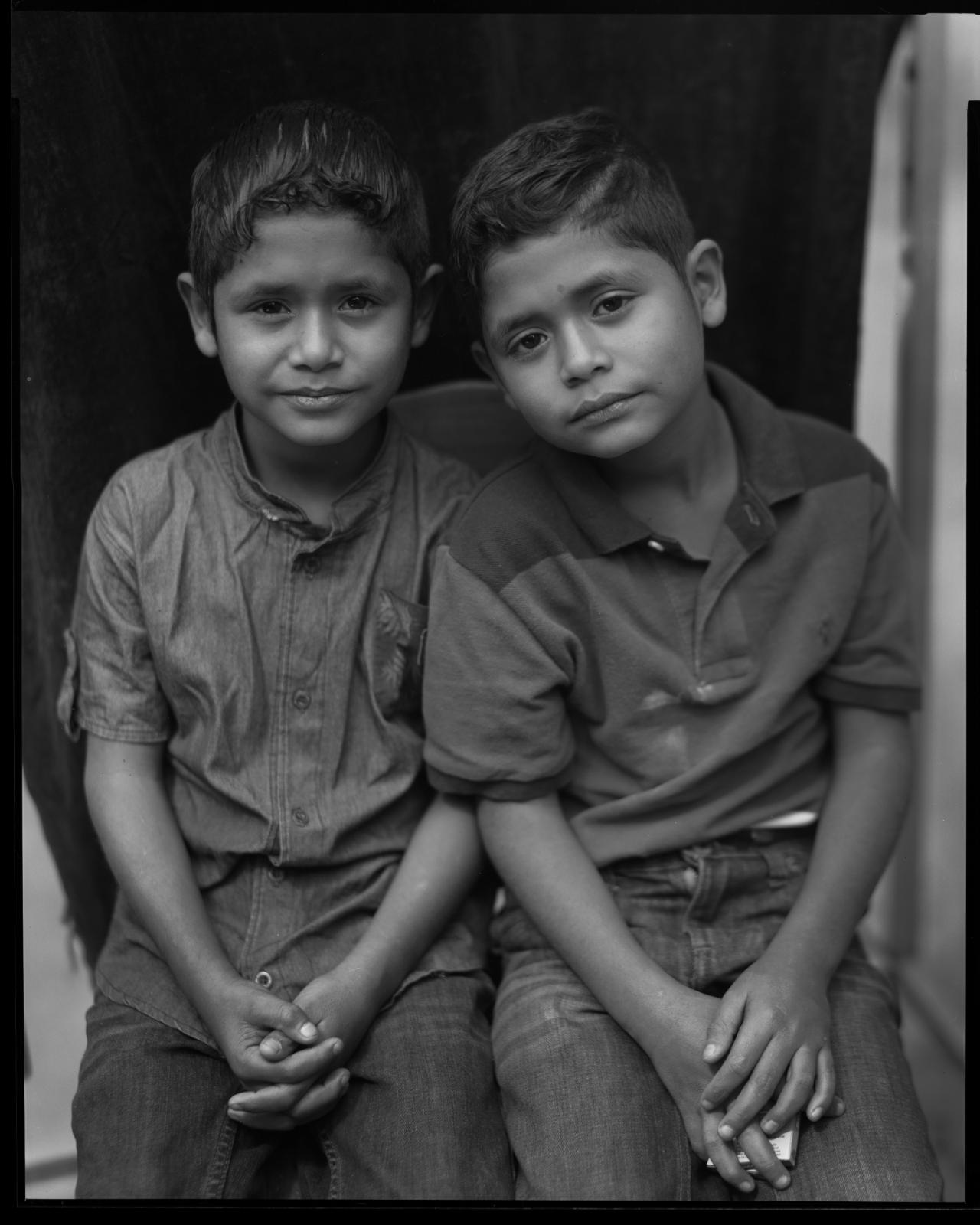

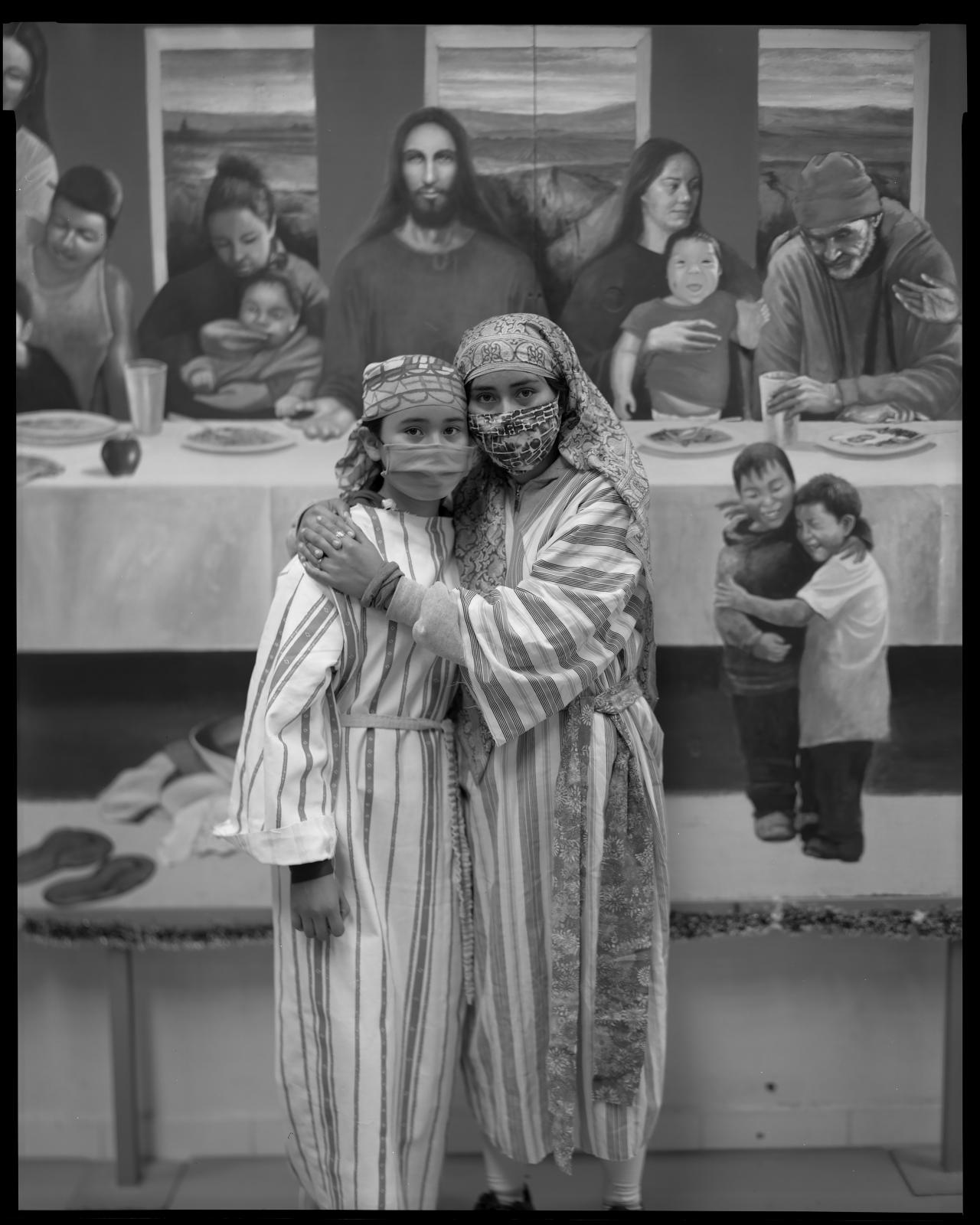

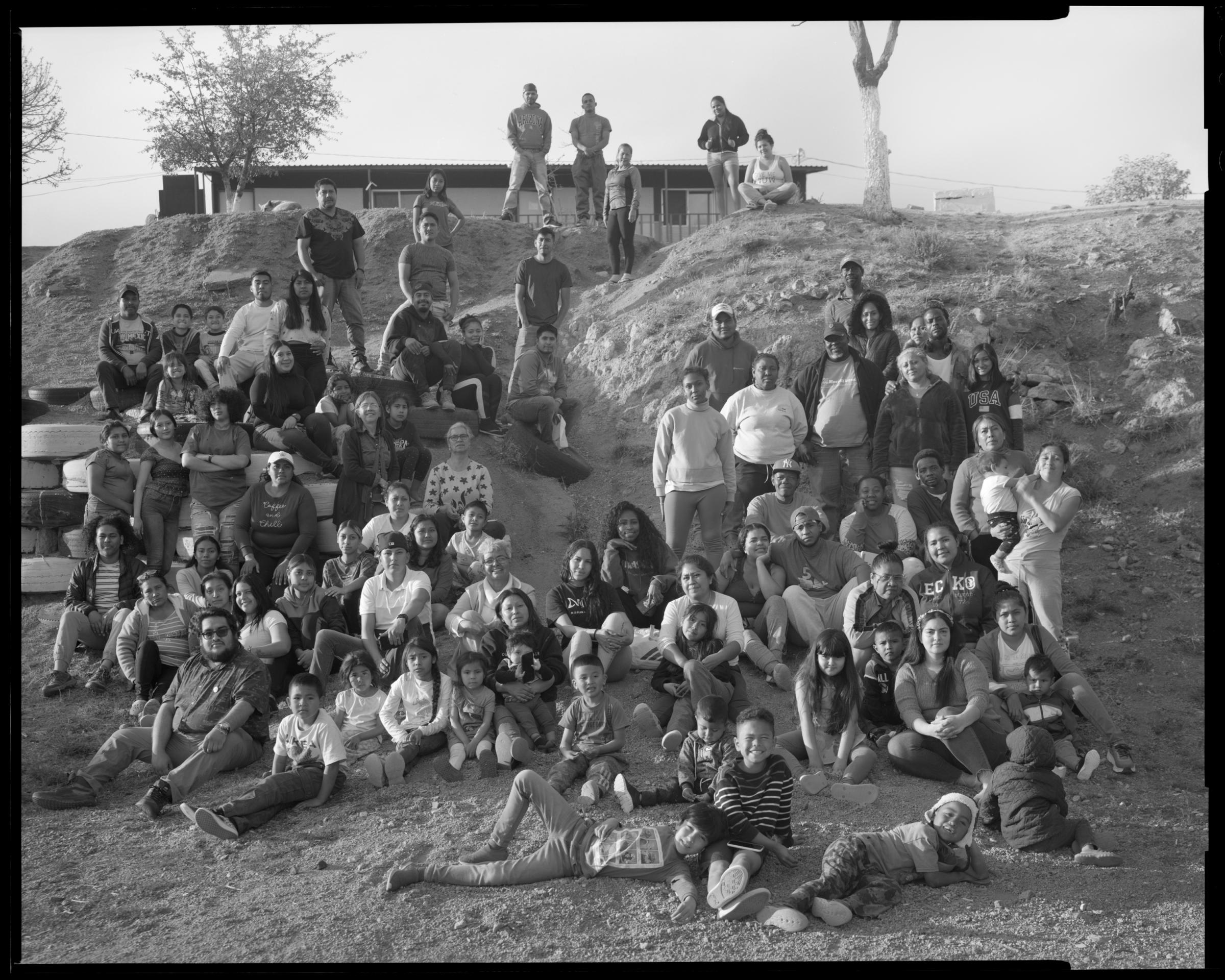

Promised Land / Tierra Prometida is a photographic body of work I have been developing since 2020. This project was inspired by and in contrast to the visual culture and discourse circulating about immigration in mainstream news during the Trump years. The rhetoric about the wall catalyzed this inquiry, propelling me to travel along the U.S-Mexico border to document and volunteer with humanitarian aid organizations like the Kino Border Initiative and Casa de la Misericordia in Nogales, Sonora, MX, Catholic Charities of the Rio Grande Valley in McAllen, TX, and Aguilas del Desierto in Ajo, AZ. Promised Land interrogates the myth of the American Dream from the perspective of the borderland environs, the people seeking asylum in the United States, and the volunteers and groups who are engaged in helping migrants with vital needs such as food, shelter, health care, as well as facilitating search and rescue in the desert.

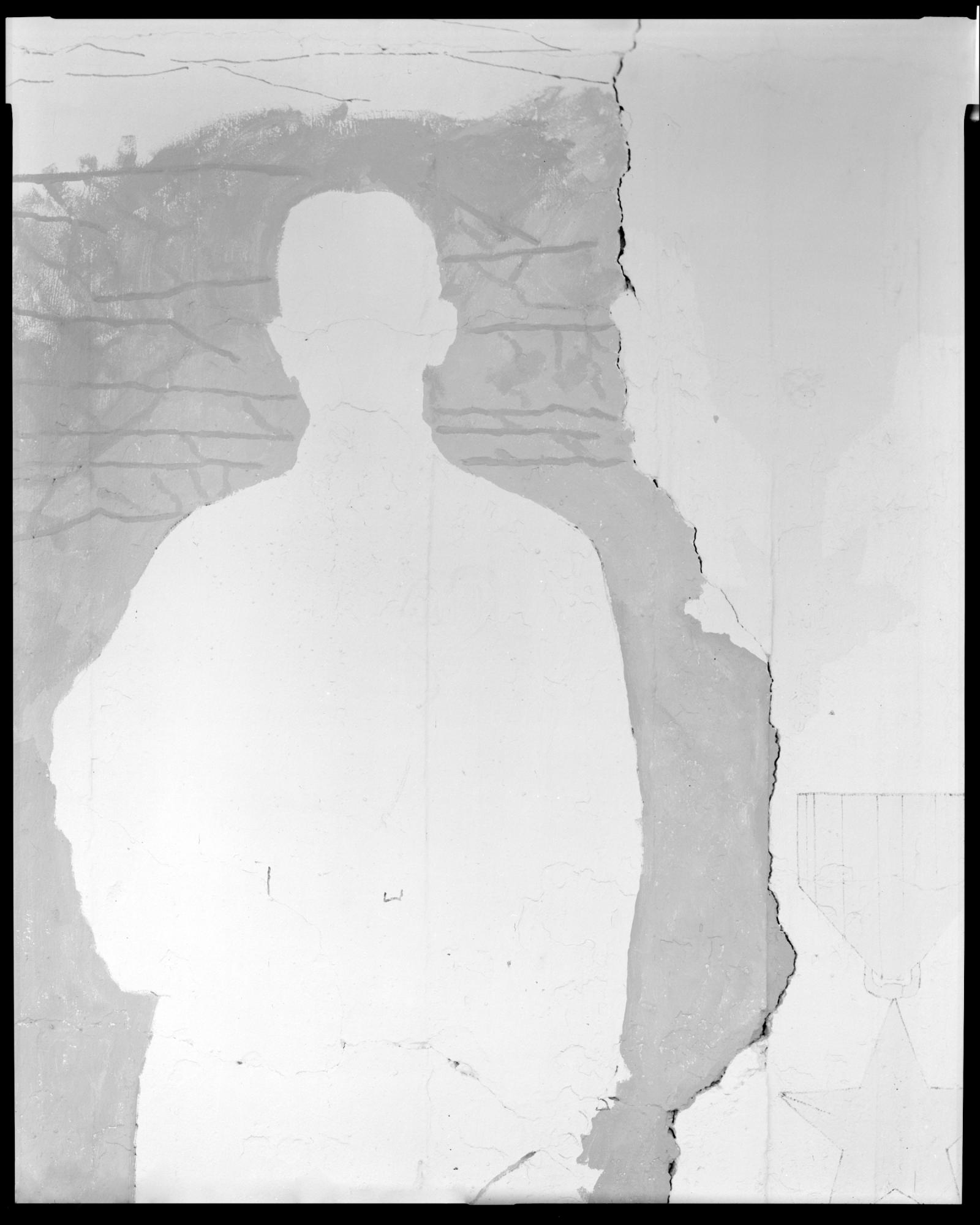

As an American photographer who grew up in an immigrant community in South Florida to a father who was a political refugee from Morocco, the unspoken specters of my family's traumatic migration stories transmitted a sense of ambiguous loss of a homeland that could never be recalled or recovered. This intergenerational burden compels me to understand how and why people are forced to flee and the ways a country like the United States continues to demonize and reject those seeking refuge and protection.

Many migrants are forced to leave their home countries because of gang violence and political persecution, climate change and water scarcity. When they arrive at the doorstep of the United States, they often find that they are unable to plead their asylum cases and are forced to wait in dangerous conditions along the northern Mexico border, small towns in which there is a strong mafia presence.

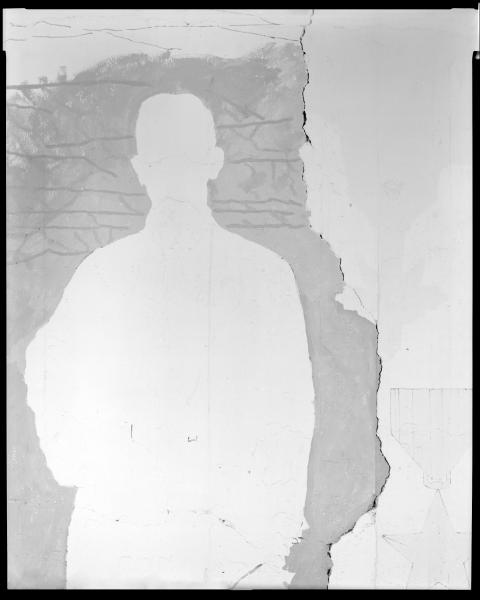

In my work as a documentarian, I am continually asking and exploring questions about how to convey a sense of both empathy and urgency in the photographs. My intent is to communicate the necessity for compassion. The large format 8x10 camera is entirely relevant: the time it takes to set up and make a photograph allows for conversation and collaboration with the person, or people, sitting in front of my camera. I hear stories and make personal connections with the people I am photographing. In a digital age, my analog images offer counter narratives to how the media depicts migration by humanizing through imagery. At the heart of it, migration is one chapter of a person's story; it is not their entire story.

Read an interview about Promised Land / Tierra Prometida in Lomography Magazine

Promised Land is a sponsored project of Fractured Atlas, a non-profit arts service organization. Contributions for the charitable purposes of Promised Land must be made payable to “Fractured Atlas” only and are tax-deductible to the extent permitted by law. To donate and for more information, visit:

https://fundraising.fracturedatlas.org/promised-land